By Estefania Lemus

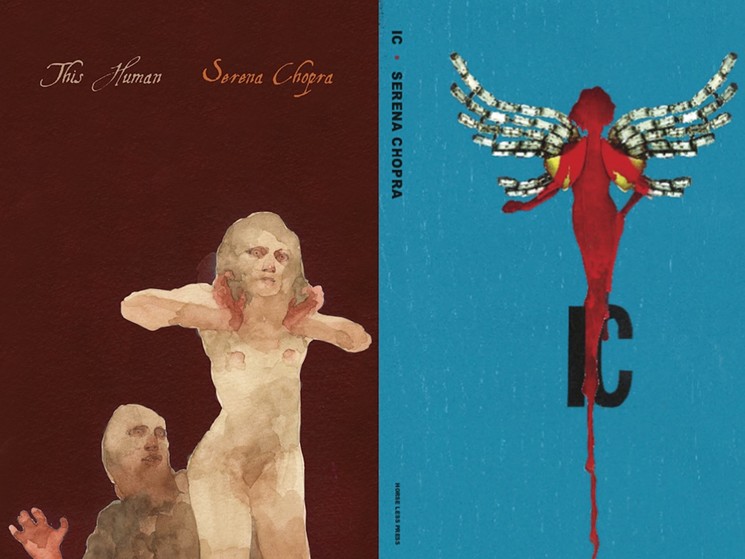

Serena Chopra is the author of This Human and Ic, as well as numerous multimedia and collaborative projects in dance, theater, visual art, and music. She'll be joining the faculty at Lighthouse, starting in the Fall Session, with the 8-Week Workshop: Intro to Personal Narrative and Memoir. We checked in with her about crossing genres, writing advice, activism, and more.

Q) When would you say you feel most at home: when you’re writing, teaching, or on stage?

A) I feel at home in each of these in different ways. Each presents challenges, which is why I try to find innovative and useful ways of challenging myself to feel at home differently in them all. If I always teach the same thing, I feel stagnant, so I always try to teach at least one book I have never read to expand my pedagogy. I also create constraints for myself when I’m writing so that I shift in aesthetic and craft and don’t get too comfortable. I like if my work is always a bit different from what I have previously done.

Q) In a recent interview, you used the word 'duende' to describe how you use translation in art. Would you say that 'duende' works as a sort of bridge between theatre, dance, and writing for you? Do you find yourself using these fields together to enhance what you want to express?

A) I actually used 'duende' (a term discussed by the poet Federico Garcia Lorca) to talk about my experience in making art—it is a term that, for me, defines the movement from creative impulse to manifestation. 'Duende' is a surging of some deep self or nature moving through the body into language, dance, sound, image, etc. I have felt 'duende' in all the art practices, forms and mediums in which I engage. I often create interdisciplinary work, using movement and text or video and textual soundscapes. I like to build a thing from the ground up, creating and composing all aspects of singular expression, such as a dance for which I also compose the sound. My work as an interdisciplinary writer uses textual expression as a means for exploring the intersection and interaction between genres, mediums and disciplines. For me, the significance of hybrid work is not simply aesthetic, though hybrid aesthetics do revel the significance of visionary alchemies. The dimensionality of hybridity provides apt articulation for the nonlinear, multi-dimensional complexes of queer (meaning, non-dominant and typically marginalized) narratives, imaginations and experiences, like my own. I blend disciplines as a means of acquiring different and expanded access to narratives and experiences that don’t always fit neatly into linear linguistic forms.

Q) How do you encourage your students to write? What advice do you give when a writer is struggling to find their words?

A) I like to introduce students to lineages of creative work across disciplines and also to poetic/artist statements in which an artist discusses and grapples with process, craft, inspiration, etc. When students recognize their struggles articulated by a well-known writer, they ease up on their expectations of themselves, and they see themselves as humans making art not artists trying to be human. When a student is struggling, I tell them to go back to what they love about writing—language, images, descriptions, rhythms—and just do that. The best advice I ever got was from a dance teacher, Gabe Masson, who told us that even if we didn’t know the steps we should just keep moving—sink into the momentum and let go of the ego. The ego is a very judgmental creature and if you get hung up on that voice, you’ll forget to be in love and have fun with your imagination and craft.

Q) In a Denver Westword interview, you talked about the challenge of legitimizing your value as a queer femme artist of color. What is it about the queer community that you want people to know the most?

A) It would be helpful for folks to recognize the effort it takes marginalized individuals to legitimize themselves to dominant cultural economies and to themselves. On top of that, marginalized artists have to nurture legitimacy for their art—something that is already hugely undervalued, monetarily and otherwise, especially when the perspective is non-dominant. As a queer woman of color, it took a lot to legitimize myself—as an artist—but also fundamentally as a body/experience. It took a long time for me to legitimize the ways I took up space and indulged my desires and passions. I think some bodies have been given sociopolitical permission to take up space and so their legitimacy is inherent to their identities. Queers, women, people of color, differently abled individuals, etc., have to work to legitimize their value—they have to put a lot of emotional, mental and physical labor towards legitimization, and even then, their legitimacy is always on the edge of dis-believability, worth-less-ness. There is a sense of anxiety that comes with being a queer artist. Our vulnerabilities do not fare well as legitimate currency in dominant social capital, and that is not only difficult but painful and exhausting.

Q) Do you consider yourself an activist? Or, would you say your writing works as an active call to change and/or recognize things that aren’t addressed?

A) I believe that folks have different skills they can contribute to activist work. For example, I am not good at organizing or taking charge—I really admire people who are—but I am good at thinking and writing, and at empathizing. I’m an observer and a cynic. I question and research and write things that I find to be helpful to myself in navigating the world and when I publish or share these things I hope that they are similarly useful to my audience. I try to speak from what I know—my narratives and experiences—and let these enter into larger cultural discussions. I also believe in the power of intimate interactions as activism. Standing up and speaking out, even in small, daily, colloquial ways, is powerful. So, I try to remind myself to have the courage to do that and to respect and listen to others as well. Listening is a great mode of activism. I try to make work that listens as much as it speaks.

Q) What plans do you have for future writing projects?

A) I have a few hybrid and interdisciplinary projects in the works. They all involve writing. My plan right now is to hold space and time for writing and thinking, and to be patient with myself as I enter into new projects and unfamiliar territory. I can feel myself moving toward a new way of making and that is exciting but also takes time, so I can’t predict much of it right now but I can tell you I’m committed to it.

Serena Chopra has a PhD in creative writing from the University of Denver and an MFA from the University of Colorado, Boulder. She's the author of two full-length books of poems, This Human (Coconut 2013) and Ic (Horse Less Press 2017), as well as two chapbooks, Penumbra (Flying Guillotine Press 2012) and Livid Season (Free Poetry 2012). She was recently featured in Harper's Bazaar, India and is currently completing a hybrid poetic memoir on queerness, trauma, and immigration. She's a 2016-2017 Fulbright Scholar, for which she is composing a text informed by her research with queer women in Bangalore, India. She's a multidisciplinary artist, working as a professional dancer, theater/performance artist, and visual artist. She's a co-founder and actor in the poet’s theater group, GASP, and worked with Denver’s Splintered Light Theater on a full-length production of Ic, for which she composed the sound score. She has an ongoing text/image collaboration, Memory is a Future Tense, with artist Lu Cong. Serena currently teaches in the MFA program at Naropa University’s Jack Kerouac School of Disembodied Poetics. Please visit SerenaChopra.com for more information.

Estefania Lemus is a fall intern at Lighthouse.