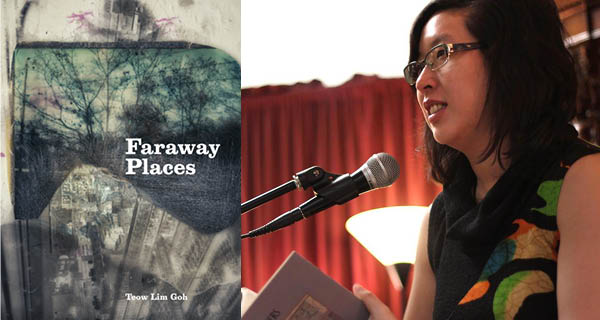

Editor's Note: On the occasion of her new collection of poems, Faraway Places, Mike Henry asked Lighthouse instructor Teow Lim Goh a few questions about her process, how her book came together, and more.

Can you talk a bit about the genesis of the book? Was there anything in this process that surprised you?

I think of Faraway Places as an accidental manuscript. When I finished writing my first book Islanders, I was both burned out and anxious to work on a new project. I could not write; it felt like my brain had stopped processing language. In this state of mind, I dipped back into my drawer of discarded drafts. I saw that there were very good reasons why these pieces didn’t work, but I also saw that some of the images radiated energy. I captured these lines and reworked them into new poems.

Everything about this process surprised me. I don’t usually write this way. I had to work from instinct. If I started to think about what I was doing, the poems would not work. I made six or seven of these poems a year. The poems seemed to belong together, but I had no idea why or how I was writing them. When I finally tried to put the poems into a book, I saw that there was an implicit story that I was trying to tell. I’ll leave it for the reader to discover, but I’ll also say that I have been learning a lot about my process as I give interviews about this book.

Often the poems have a kind of logical progression to them—a statement is made, then another, related idea presents itself, and the reader is somehow pressed to explore how they relate. Kind of a proof—if this is true, and this also is true, then…. But the conclusion, or “then” statement isn’t always presented in the poem, which is something I love about the book. Was this a conscious decision, and if so, how does it relate to the theme of faraway places, and the motif of maps?

Like I said, in these poems I had to work from instinct rather than make conscious decisions. It did occur to me that the “faraway places” in the title are not just the literal places of nature and travel, but also the distances from the self. I was raised in an environment where I had to deny or give up crucial parts of myself, and for a long time I felt that I could only look at myself as an outside observer.

In hindsight, I believe I was trying to make maps for myself through writing. In the drawer of drafts that seeded these poems, I was contending with the pain of being detached from myself and unable to inhabit my body. On some level, I think of Faraway Places as a private dictionary, the “entries” here an accumulation of symbols in dialogue with each other. Metaphors, after all, are maps—they create constellations of meanings and associations that help us fathom the world.

I was a math major back in the day, so maybe the deductive argument of proofs is second nature to me, for I did not notice I was doing that in Faraway Places. As for the absence of conclusion—I suppose I was trying to use metaphor to express what is difficult for me to say directly, letting the reader make the leaps and create their own maps.

Your writing is so elegiac and yet so compressed, and your use of white space subtle yet haunting. Can you talk a little about how you go about creating this mood, and how you perceive white space working in a poem?

I came to this mood on the page subconsciously. But I can say a few things about it. Like I said, when I wrote the poems, I did not know what I was doing, but when I put them together into this book, I saw that there was an implied story. In a way, these poems are written from the residues of experience. The white space is first and foremost the deliberate absence of narrative.

Most of my poems outside of Faraway Places are persona poems rooted in history and archival research, which is to say, I often engage with narrative. But I see similarities in my approaches: in those poems, I also use white space to suggest absence, whether it is something left unsaid or what the character cannot reveal even to themselves.

The line break in poetry can be used to create pauses or reinforce repetitions in the rhythm. These cadences mimic the shifts and tremors of the mind, suggesting there is more to what can be seen on the page.

These poems are somehow intimate, yet also open to a wide audience. Is there a specific persona being addressed? Can you talk a little bit about how this level of direct address works in the book?

Some of these poems are implicitly addressed to specific people, including artists whose work inspire me. Along the way, I saw that the identities of the addressees were less important than the ideas and emotions captured in the poems. You could say that these poems are ultimately a dialogue with the self and the persona being addressed is a version of myself. In some cases, I was aware that I was talking to a younger version of myself.

What are you working on now?

I finished writing two other books over the past year: Western Journeys is an essay collection rooted in my travels in the past decade, including the adventures that led me to my ongoing project to recover the stories of Chinese immigrants in the American West. The early drafts of many of these essays were the source texts for Faraway Places. And Bitter Creek is an epic poem on the massacre of Chinese miners in Rock Springs, Wyoming, in 1885.

Now I’m taking a break from writing for publication. I have some ideas of what I might work on next, but mostly I’m observing and taking notes.

Teow Lim Goh is the author of Faraway Places (Diode Press, 2021), and Islanders (Conundrum Press, 2016), a volume of poems on the history of Chinese exclusion at the Angel Island Immigration Station. Her work has been featured in Tin House, Catapult, PBS NewsHour, Colorado Public Radio, and The New Yorker.